Definition: What is jaw cancer?

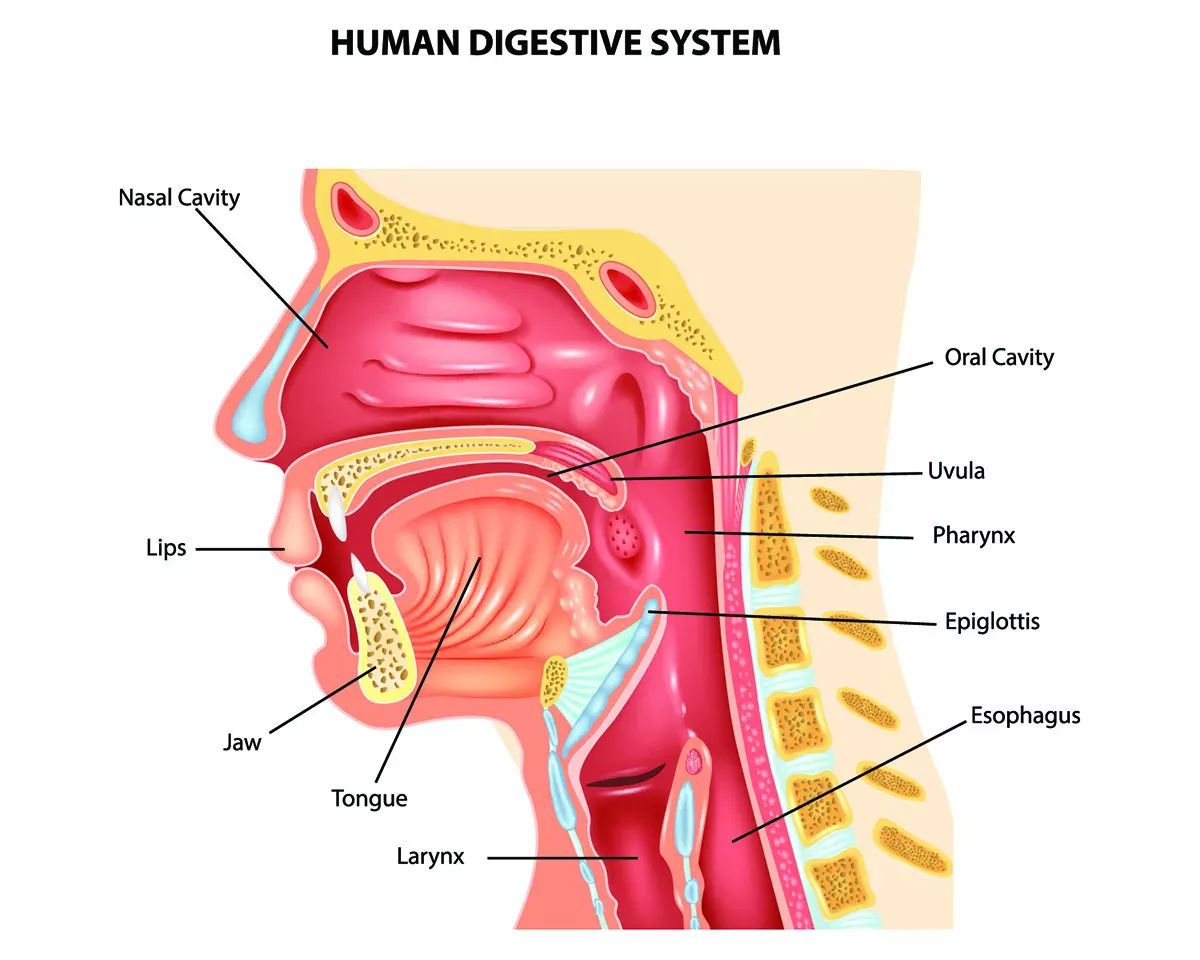

Jaw cancer is a more colloquial term encompassing various cancers impacting the jaw. In medical classification systems like ICD, there is no distinct category solely for jaw cancer, unlike specific categories for gum, floor of the mouth or lip cancers. The lack of a distinct category for jaw cancer arises because most malignant tumours affecting the jaw do not develop in the actual jaw but result from metastases or spread from neighbouring tissues like the gums, floor of the mouth or base of the tongue. Around 90 percent of mouth and throat cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, originating from the top layer of the oral mucosa. Cancers originating directly within the jawbone are far less common.

Throughout this article, the terms "jaw cancer" and "jawbone cancer" encompass all malignant tumours within the jaw area. Typically, cancer cells within the jaw displace healthy bone cells, proliferating uncontrollably and forming a tumour. Jaw cancer can form in both the upper and the lower jaw.

What does jaw cancer look like?

The majority of tumours developing within the jaw are benign and therefore do not fall under the category of "jaw cancer". Hence, we will not delve into further details about them here. Below, you will discover an overview of various malignant tumours impacting the jaw, accompanied by images illustrating what jaw cancer may look like. Please be aware that the images depict advanced-stage jaw cancer. During the early stages, jaw cancer may appear less prominent and might be mistaken for different dental or gum diseases. Find out how to recognise jaw cancer in the section on symptoms.

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most prevalent type of jaw cancer. It typically spreads from adjacent tissues to the jaw. In particular tumours in the gums, floor of the mouth and base of the tongue have a tendency to impact the jawbone.

A less common subtype is primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma, which is a rare malignancy of the jaws. The term "intraosseous" means "originating from within a bone". This type of tumour is believed to develop from the remnants of the odontogenic epithelium (dental lamina) with no initial connection to the oral mucosa.

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma of the jaw is a form of bone cancer. It is rare, representing less than one percent of all malignant tumours in the oral cavity. The mutated cancer cells stem from the bone matrix.

Ameloblastoma

Ameloblastoma is typically a benign tissue growth that exceptionally and rarely progresses into a malignant tumour. It originates from ameloblasts, i.e. epithelial-derived cells, and aggressively invades bone marrow spaces. If left untreated, it can grow significantly, causing substantial alterations to the jawbone and severely limiting jaw functionality. For example, there may be difficulties in chewing, swallowing and speaking. Ameloblastomas are more commonly found in the lower jaw and typically necessitate surgical removal even if they are benign.

Frequency of jaw cancer

There are no specific figures available for the frequency of jaw cancer as it is not categorised officially as a distinct type of cancer. Approximately 200,000 to 350,000 individuals worldwide are diagnosed with oral cavity cancer every year. In Germany, there are around 12,000 new cases of oral cavity cancer reported yearly; while in Switzerland, the number stands at around 1,200 cases.

Symptoms: How does jaw cancer manifest itself?

Unlike other types of oral cavity cancer that frequently go unnoticed for extended periods, jaw cancer is often detected early during dental check-ups through X-ray images.

The following signs may also indicate jaw cancer:

- Ulcers

- Swelling (in the mouth or face)

- Sores that do not heal

- Frequent bleeding from the mouth

- Red or white patches in the mouth

- Bad breath

- Difficulty in speaking

- Difficulty in opening the mouth

- Loose teeth

- Sensitivity to pressure

- Jaw and/or ear pain

- Numbness in the teeth, lip and chin area

- Pain or difficulty in swallowing

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Dentures that suddenly no longer fit

Metastases: Where does jaw cancer spread to?

Jawbone cancer in the form of osteosarcoma metastasises mainly via the bloodstream, targeting the lungs. However, metastases can also occur in the skeletal system. In contrast, squamous cell carcinomas primarily generate metastases within the lymph nodes and can spread to distant locations through the lymphatic system.

Causes: How does jaw cancer develop?

Cancer always occurs when mutated cells carrying altered genetic information are not recognised by the immune system and displace healthy cells. Mutated cells multiply significantly faster than normal cells. Resulting in the development of a malignant tumour.

The exact reasons behind the cell mutations responsible for triggering jawbone cancer are not yet fully known. However, there are a number of risk factors for jaw carcinomas that increase the likelihood of developing jaw cancer. That said, these factors apply solely to squamous cell carcinomas originating in another region of the mouth and spreading to the jaw, not to osteosarcomas developing directly within the jaw.

Smoking and drinking

The leading risk factor for oral cavity cancer, overall, is the combination of smoking tobacco and drinking alcohol on a regular basis. In fact, smokers who also drink alcohol regularly are 30 times more likely to get oral cavity cancer. While the risk for smokers who do not drink alcohol at all is 10 times higher.

Betel chewing

In Southeast Asia, in particular, chewing a mixture of betel leaves and betel nuts (also known as areca nuts) is a very popular way to boost energy levels between meals. Unfortunately, this stimulant is also carcinogenic, leading to a much higher incidence of floor of the mouth cancer in Southeast Asia compared to Europe or North America. Floor of the mouth cancer can also infiltrate the jaw.

Human papillomaviruses (HPVs)

If jaw cancer initially developed in the throat area, such as the tonsils or the base of the tongue, and subsequently spread to the jaw, human papillomaviruses (HPVs) could potentially be responsible. The virus is typically linked to cervical cancer but can also be transmitted through oral sex, thus contributing to the development of cancer in the throat and jaw region. In cases where younger individuals develop oral cavity cancer, human papillomaviruses (HPVs) often play a role.

Poor oral hygiene

There is evidence suggesting that inadequate brushing habits and tooth loss might contribute to the risk of oral cancer. Individuals affected by periodontitis also seem to face an elevated risk. Ill-fitting prostheses that cause chronic inflammation are also suspected of potentially triggering cancer.

Good to know:

Even though we brush our teeth daily, we frequently make inadvertent mistakes without realising it. Discover the – scientifically proven – correct tooth brushing technique in our instructions:

Age

The risk of developing jaw cancer is typically higher in older individuals than in younger ones. Oral cavity cancer occurs most frequently in men aged 55 to 65 and in women between 50 and 75 years of age.

Diagnosis: Who diagnoses jaw cancer?

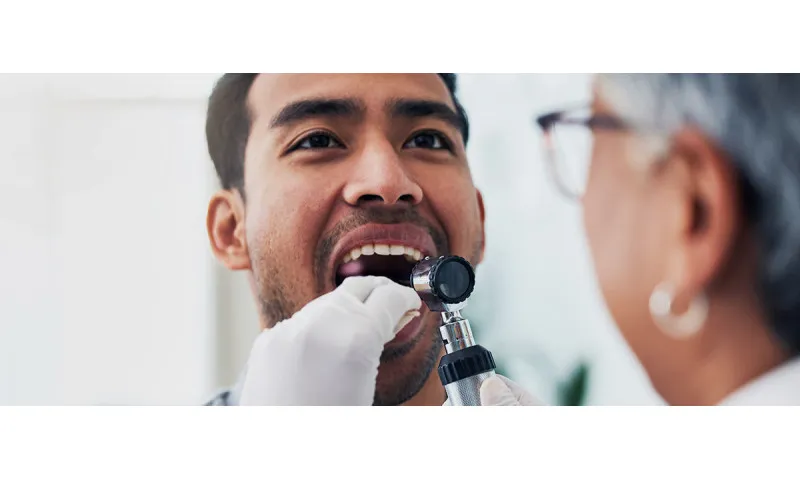

Jaw cancer is often discovered by a dentist: Those affected usually experience a swelling or ulcer in the jaw area or notice that teeth are suddenly loose, prompting them to seek advice from a dentist. However, the tumour can also show up completely unexpectedly on an X-ray image without the affected individual experiencing any prior symptoms.

If jaw cancer is suspected, the dentist typically refers you to a specialist in oral and maxillofacial surgery for further evaluation. The first step in diagnosing cancer is a biopsy during which a doctor takes a sample of tissue from the affected area, which is then analysed in a laboratory. Experts can directly determine the presence of a malignant tumour and its specific subtype from the tissue sample. The biopsy involves the insertion of a needle into the jawbone to extract a small tissue sample while the area is numbed with local anaesthetic. Subsequently, the wound is sutured.

Upon confirmation, further imaging examinations are typically conducted to assess the extent of the cancer. This may include the following examination methods:

- X-ray image of the upper and lower jaw

- Ultrasonic scan of the lymph nodes

- Computed tomography (CT) scan

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

The specialist uses the results to classify the tumour. The decisive factors here include the size of the tumour, invasion into adjacent tissue, lymph node involvement and the presence of distant metastases.

Good to know:

You can find out exactly how the classification system for tumours works in our main article on oral cavity cancer:

Treatment: How is jaw cancer treated?

A team of specialists always collaborates to treat jaw cancer, pooling expertise from various medical disciplines. In so-called tumour conferences or tumour boards, experts review each case to devise the most effective treatment plan for the individual. Generally, surgical removal of the tumour is the standard course of action. Depending on the location, size and stage of the tumour, treatment plans often include radiotherapy or chemotherapy, either before or after surgery.

The primary objectives of jaw cancer treatment are:

- To remove the tumour completely

- To preserve or restore jaw function and facial appearance as effectively as possible

- To prevent recurrence of the tumour

Good to know:

Unfortunately, cancer treatment has adverse effects on oral and dental health. Find out everything you need to know on how to protect yourself and minimise the side effects in our article:

Surgery for jaw cancer

Depending on the size and location of the tumour, surgery for jaw cancer can be very complex. With small tumours, preservation of the jawbone is feasible. With larger tumours, parts of the jawbone often need to be excised completely to ensure that the entire tumour is removed. Research indicates that a wider excision with more extensive tissue removal correlates with better prognoses and increased chances of survival for patients. If other parts of the oral cavity, for example part of the tongue, are impacted, they must also be removed surgically.

Reconstruction: What does jawbone reconstruction involve?

If large parts of the jaw or even a complete lower or upper jaw are removed, complex reconstructive procedures are necessary to restore jaw function and facial appearance. To do so, the surgeon extracts bone, muscles, skin and blood vessels from areas like the shoulder or fibula to craft a new jawbone. Vascular transplantation is crucial to ensure a sufficient supply of blood to the new jawbone and to prevent tissue from dying. Metal plates can be used for stabilisation. Several follow-up surgical procedures are usually required to complete the reconstruction process.

Modern reconstruction techniques often restore normal chewing and speech functions for individuals affected by jaw cancer, although relearning these abilities may be necessary in some instances. As the removal of the jaw severely impairs both jaw function and facial appearance, successful jaw reconstruction often restores quality of life for those affected.

Good to know:

Brushing your teeth immediately after surgery is usually unpleasant. The CS Surgical toothbrush from Curaprox has been specifically designed for oral care after surgery and can be highly beneficial during this period. The mouthwashes, gels and toothpastes of the Perio plus range utilise chlorhexidine to locally control bacteria and aid in the healing process.

Radiotherapy and chemotherapy

The decision of whether radiotherapy or chemotherapy is needed before or after surgery is determined for each specific case by specialists during the tumour conference. Radiotherapy of the jawbone in particular can cause severe side effects – potentially resulting in the death of the jawbone in extreme cases. Early detection of the tumour can sometimes allow for treatment without the need for chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Find more information on radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the main article on oral cavity cancer:

Prognosis: What are the chances of surviving jaw cancer?

Unfortunately, precise figures regarding life expectancy and survival rates for jaw cancer are not available. In the case of oral cavity cancer in general, early detection significantly improves a patient's chances of recovery. When detected early, recovery rates range from 80 to 90 percent. Unfortunately, 70 percent of oral cancer cases are only discovered at an advanced stage, which significantly worsens the prognosis. Oral cavity cancer can be fatal if it has metastasised to vital organs.

At this point, we cannot make any generalised statements, as treatment outcomes and durations vary significantly among individuals.

Good to know:

Find a comprehensive list of vital addresses for cancer patients, including counselling and support resources in the "blue advisor" (blaue Ratgeber) published by German Cancer Aid (Deutsche Krebshilfe).

Sources

Bertin, Hélios et al.: Osteosarcoma of the jaws: An overview of the pathophysiological mechanisms, in: Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2020.

City of Hope: Jaw cancer, at: cancercenter.com.

Der Spiegel: »Man wird sich eine Weile wehren« Krankengeschichten prominenter Krebsopfer, Edition 27. 1987.

Düker, Jürgen: Odontome, in: Röntgendiagnostik mit der Panoramaschichtaufnahme. Thieme 2000.

Ferrari, Daris et al.: Osteosarcoma of the Jaw: Classification, Diagnosis and Treatment, in: Osteoscarcoma - Biology, Behavior and Mechanisms. IntechOpen 2017.

Gesellschaft für Sexualwissenschaft e.V.: Oralsex kann Tumor im Mund-Rachen-Bereich auslösen.

Gesund.bund.de: ICD-Code-Suche.

Goetze, Elisabeth: Osteosarkom des Unterkiefers, at: zm-online.de.

Goetze, Elisabeth: Das unerkannte Plattenepithelkarzinom, at: zm-online.de.

Ha-Phuoc, An-Khoa et al.: Navigierte OP unerlässlich: Bösartiger Tumor im Mittelgesicht, at: zwp-online.info.

Health Central: Jaw Cancer: Everything You Need to Know.

Krebsliga: Mundhöhlenkrebs.

Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e. V. (AWMF), der Deutschen Krebsgesellschaft e. V. (DKG) und der StiftungDeutsche Krebshilfe: Patientenleitlinie Mundhöhlenkrebs.

Nölken, R. et al.: Primäres intraossäres Plattenepithelkarzinom auf der Basis einer odontogenen Zyste – eine Falldarstellung, at: prof-noelken.de.

Onkopedia: Osteosarkome.

Mayo Clinic: Jaw tumors and cysts.

Montero, Pablo et al.: Cancer of the oral cavity, in: Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America. 2015

Mühlenkreiskliniken: Wenn aus dem Bein ein Kiefer wird.

Mund-Kiefer-Gesicht Chirurgie Dr. Dr. Hendrik Fuhrmann & Kollegen: Mundhöhlenkrebs – Diagnostik und Behandlung.

MVZ - orale Chirurgie, Kieferchurgie, Implantologie und operative Parodontologie: Knochenbiopsie als diagnostische Gewebeprobe.

Schiff, Bradley A.: Kiefertumoren, at: MSD Manual. Ausgabe für medizinische Fachkreise.

Singh, Annu et al.: Osteoradionecrosis of the Jaw Following Proton Radiation Therapy for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer, in: JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery. 2022.

Stern: Claudia Gülzow. TV-Maklerin war an Krebs erkrankt.

Universitäts Spital Zürich: Ameloblastom des Kieferknochens.

Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg: Krebserkrankungen im Mund-, Kiefer- und Gesichtsbereich.

Ziebart, Thomas et al.: Intraossäres Plattenepithelkarzinom, at: zm-online.de.

All websites last accessed on 10 September 2023.

Swiss premium oral care

Swiss premium oral care